GLOBAL ECONOMICS AND POLITICS

Leo Haviland provides clients with original, provocative, cutting-edge fundamental supply/demand and technical research on major financial marketplaces and trends. He also offers independent consulting and risk management advice.

Haviland’s expertise is macro. He focuses on the intertwining of equity, debt, currency, and commodity arenas, including the political players, regulatory approaches, social factors, and rhetoric that affect them. In a changing and dynamic global economy, Haviland’s mission remains constant – to give timely, value-added marketplace insights and foresights.

Leo Haviland has three decades of experience in the Wall Street trading environment. He has worked for Goldman Sachs, Sempra Energy Trading, and other institutions. In his research and sales career in stock, interest rate, foreign exchange, and commodity battlefields, he has dealt with numerous and diverse financial institutions and individuals. Haviland is a graduate of the University of Chicago (Phi Beta Kappa) and the Cornell Law School.

Subscribe to Leo Haviland’s BLOG to receive updates and new marketplace essays.

A key United States interest rate benchmark, the 10 year Treasury note, probably established a major bottom around 1.40 percent in late July 2012.

The Federal Reserve Board’s fixing of the Federal Funds rate at exceptionally low levels admittedly restrains ascents in US government yields. Its benevolent promise and determination to maintain the Funds rate almost flat on the ground until at least mid-2015 encourages faith that government yields generally will remain depressed. Also, heightened flight to quality fears and nervous leaps in recessionary worries may push the 10 year UST challenge back toward or even slightly beneath its July low. The Eurozone crisis, for example, has not disappeared. America’s 2013 federal “fiscal cliff” looms large on the horizon.

However, all else equal, a flood of money printing tends to increase inflation and thus interest rates. And all else equal, cracking or crumbling creditworthiness for a borrower- whether an individual, corporation, or government- tends to boost the interest rate charged that borrower. America nowadays confronts another round of Federal Reserve money printing and has made little headway in resolving its awesome fiscal problems.

The Federal Reserve’s long rumored (fervently hoped for) and recently decreed (9/13/12) third cascade of money printing, QE3, probably will be massive, perhaps over one trillion dollars. Over time, this deluge will help to boost US government (and other) interest rates.

Moreover, given a generous desire to avoid the fiscal cliff and a downturn, Congress probably will continue its huge deficit spending spree. Not only has America become habituated to deficit spending, debt (including personal debt), and assorted forms of entitlement. How many people volunteer nowadays to pay sufficiently more taxes to solve- or at least significantly reduce- near term (as well as long run) national fiscal troubles? For a debtor nation such as America, running substantial budget deficits alongside elevated (and thus expanding) government debt as a percentage of nominal GDP raises the risk of a severe fiscal trial. The arrival of this crisis probably will occur relatively soon rather than at some vague date many years down the road. In any event, this visit will tend to raise US government rates. The US may be an economic fortress, but that does not guarantee that its creditworthiness will be unquestioned or unchallenged. Witness Europe in recent years; also recollect the debt sagas of many emerging marketplaces.

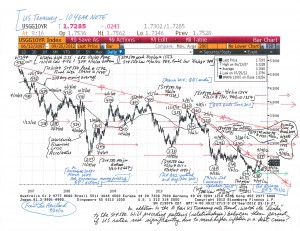

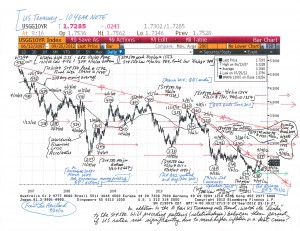

What are key levels for the US Treasury 10 year note? Start at the low end and walk higher.

FOLLOW THE LINK BELOW to download this market essay as a PDF file.

Fed Fixations- Interest Rates (9-24-12)

US Treasury 10 Year Note Chart (9-24-12)

The broad real trade-weighted United States dollar will depreciate. Over the next several months, its retreat probably will reach July 2011’s record low around 80.6 (for the nearly four decades going back to 1973, monthly averages; March 1973=100) and break beneath it, with around 77.0 a reasonable target. Over the longer term, a descent to around 72.5 to 75.0 would not be surprising.

We know that all else equal, debtors (and borrowers) want as low an interest rate as they can get.

The Fed’s interest rate policy is (and has been for several years) geared toward aiding debtors (borrowers) at the relative expense of creditors (savers). Since debtors deserve special Fed help, surely the unemployed do.

We know that all else equal, debtors in a home currency (imagine the beloved US dollar) tend to enjoy some modest home currency depreciation. This makes their debt obligations less burdensome to pay off. This perspective assumes that these debtors can keep borrowing fairly easily, and at interest rates that not too high (overly punitive).

However, all else equal, foreign creditors are not enamored of such currency degradation. Foreigners hold an enormous amount of US Treasury securities, nearly $5.3 trillion (as of June 2012,

What happened to the US dollar after the Fed’s prior two massive rounds of quantitative easing? The TWD depreciated.

Significantly, the Fed’s determination to keep interest rates pinned to the floor (and thus offering pitiful returns on government debt relative to inflation) for an extended time period, say out to mid-2015, boosts the odds that its QE3 money flood will help to push the dollar down. In addition, recall that he TWD has been in a declining pattern over the past decade (or longer). So has America’s relative international economic and political prominence. Remember that QE3 is occurring alongside substantial US indebtedness (with a potential federal deficit disaster lurking on the horizon), a noteworthy current account deficit, and only modest domestic savings (compare Japan).

The Fed presumably is aware that the TWD declined after the QE1 and QE2 episodes. So apparently the Fed will tolerate dollar weakness to achieve its employment objectives.

FOLLOW THE LINK BELOW to download this market essay as a PDF file.

Fed Fixes and Dollar Depreciation (9-17-12)

Since the current economic crisis emerged in 2007, a rough pattern has been that major movements and levels in US Treasury ten year note yields have preceded or coincided with those in the S+P 500. Thus, “in general”, plummeting UST yields have been paralleled by diving stock prices. And rising interest rates are connected to rallies in stocks. So in today’s world, gurus and guides often underline that higher and higher UST rates fit an economic recovery (health) scenario. In contrast, collapsing rates indicate looming (or actual) disaster; hence the popularity of flight to quality and safe haven commentary in regard to UST. Such relationships between the UST 10 year note and stocks (and variables allegedly bound to them) of course help forecasters to assess probabilities for and predict important debt and equity trend changes. Looking forward, this ongoing pattern may well persist.

Yet at some point, and arguably within the next several months, the present relationship between the US ten year and the S+P 500 may change. Thus rising UST yields eventually may coincide with sinking stocks. What key trading levels for the 10 year should one keep an eye out for? Such trigger point ranges will vary over time. So anyway, what guidelines for nowadays? If the US 10 year note yield floats decisively above the 2.50 percent level, and if stocks rally very little as that yield barrier is breached, that would hint the current (2007-2011) UST/S+P 500 relationship is altering.

As the global economic crisis flows on and on, many of its intertwined actions and participants (and thus marketplace relationships) may remain relatively unchanging. But they are not stagnant. Today’s marketplace voyagers should wonder if the crisis has drifted closer and closer to a new round of difficulties. Look at European yields, and place Germany on the sidelines. Focus instead on Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy. These countries show that severe economic problems (and downturns) are not always or inevitably associated with falling (or low) government interest rates.

FOLLOW THE LINK BELOW to download this market essay as a PDF file.

Marketplaces and Policies – Making Connections (11-29-11)